This masterful portrait by Tintoretto manages to capture the character of Mary Magdalene in all of her popular contradictions. Juxtaposed with the crucifix and skull (a clever reference to Golgotha - “the place of the skull” - as the hill where Jesus died), she herself is fully in the bloom of life and youth. Centered between the light of both the sun and moon (noticed how both are partially obscured in Tintoretto’s expert chiarascuro technique), she turns to gaze at the rays of the sun, made more brilliant by the cover of clouds. Most contradictory of all is the figure of Mary herself, somehow depicted as both modestly clothed and nude at the same time; her form is lively, sensuous, sexy even — yet her demeanor projects the quintessence of chaste devotion.

Who is this woman?

Readers well-read in feminist criticism might well see her as the perfect projection of the male gaze: the ultimate Madonna, the ultimate Whore, all in one. This is not wrong, in my view; yet beneath that layer of recognition, I see profound, esoteric symbolism which brings us closer to understanding this enigmatic woman whose character has been both slandered and redacted for centuries.

The Revolutionary Divus

Last week, I explored the depiction of Jesus as a divus in the canon Christian gospels. This Latin word references a kind of god — or demigod, if you prefer — who began their life as a human mortal before ascending to the heavens of Olympus to join the pantheon of Dei, who were the “original” gods who have always been gods. So Jupiter was a deus and Vesta was a dea, whereas Romulus, Hercules, more than two dozen Roman emperors and — if I’m correct — Jesus Christ all belong to the category of divus, beings who were born as mortals but then ascended into heaven as a sort of second-tier god.

Looking back at last week’s post, I regret that I didn’t write more about the implications of this reading for orthodox Christian thought. I regret it because when one examines some of the earliest Christian writing, such as the letters of Paul, one can easily understand why the nascent Christian movement proved such a threat to the Roman imperial order.

As discussed last week, by far the most common instances of divii encountered in the earliest centuries of Christianity were the Roman emperors. The Roman imperial religion promoted the majority, though not all, of the dead emperors as ascended divii, to be worshiped at temples throughout the Empire. Devotion was not a question of faith; it was compulsory. Significantly, the Roman imperial religion crafted a powerful divide between the ruler and ruled; the myths of the spiritual ascent of emperors (brilliantly satirized in Seneca’s Apocolocyntosis) emphasized for everyone else in the empire how they, mere subjects of imperial rule, could never do the same. Olympus was reserved for gods, mythical heroes, and emperors — none else need apply.

Then, along came Christianity.

Christian myth tells the story of how a humble carpenter from the backwater shithole of Nazareth, born a mere human babe, ascended to heaven to sit at the right hand of the Jewish God. In this heaven, there’s no Zeus, no Isis, no Marduk — and definitely no Roman emperors. Only the Father and the Son, hanging out, until — and here’s the real kicker — comes the Day of Judgment, when they will fling the doors open wide, come one, come all. And on that day, everyone, from the richest noble to the lowliest slave, can enter in — if they have been initiated into the Christian mysteries. The emperors and their ilk will find the gates barred; the weight of their haughty pride will drag them down to their eternal comeuppance. The first shall be last, and the last shall be first.

When one fully appreciates how completely the Christian story upended the propaganda of the imperial cult, it becomes easier to understand why the Romans, otherwise famous for their religious tolerance, cracked down so violently on the Christians martyrs. Their central figure appropriated the honorific reserved for the living emperor — filus divi, son of god — and stole its power. The more the new faith spread across the Empire, the more of an existential threat it began to pose to the emperor’s legitimating myths.

Mary as Diva?

So far, I’ve mentioned mostly male gods and demigods. Partly, this is a reflection of the available evidence; from what can be gleaned at this distant date, it seems that most of the divii worshiped in the Roman imperial religion were men.

Most — but certainly not all.

The Romans worshiped a polytheistic pantheon which included deities of diverse genders. Some were male, some were female and some, like Hermaphrodite, were transgender. Thus, it shouldn’t be too surprising to learn that quite a few of the worshiped divii of the Roman imperial cult were actually divas — deities who were born as women, then ascended as goddesses.

Inevitably, this happened through family connections. Mary Beard relates that the emperor Nero successfully arranged for his infant daughter to be declared a goddess after her untimely death, though there is no known evidence that the cult of the baby princess actually took off in any meaningful way. Far more significant was the cult of Livia Drusilla, the widow of Augustus Caesar and mother of the Emperor Tiberius; after her late husband had been declared an ascended divus by the Senate, she pulled enough strings to have herself bestowed with the same honors. Boosted, no doubt, by her considerable wealth and estates, her cult continued to endure for centuries after her death.

In that context, I thought it worthwhile to ask: if the Christian gospels depict Jesus as a divus, does that make Mary Magdalene, his widowed wife, a diva? After all, Mary’s character in the gospels appears to follow the same template as Livia Drusilla (who, in an unlikely coincidence, died in the same year in which Jesus was supposed to have been crucified). Both women were the wives of great men who ascended into heaven to join the god(s); both remained behind as widows and witnesses, the most intimate companions of the filus divi.

The parallels are fascinating, but as I dove deeper in my research I realize that Mary Magdalene’s character is a bit more complex. Her character evokes the famous divas of the imperial cult, for sure; but just as the character of Jesus cleverly twists the myth of the Roman emperor, so too does Mary’s offer a new spin, and a cutting criticism, of the cult of the divas like Livia Drusilla.

The “Pleroma of the Pleroma”

Elaine Pagels, in The Gnostic Gospels, mentions a curious honorific bestowed on Mary Magdalene by those long-suppressed but recently rediscovered texts. Those suppressed gospels call her “the pleroma of the pleroma” — an anaphora of an esoteric Greek word which could be translated either as “fullness/wholeness” or “perfection”, depending on context.

What does this strange title mean, and what does it have to do with the diva archetype?

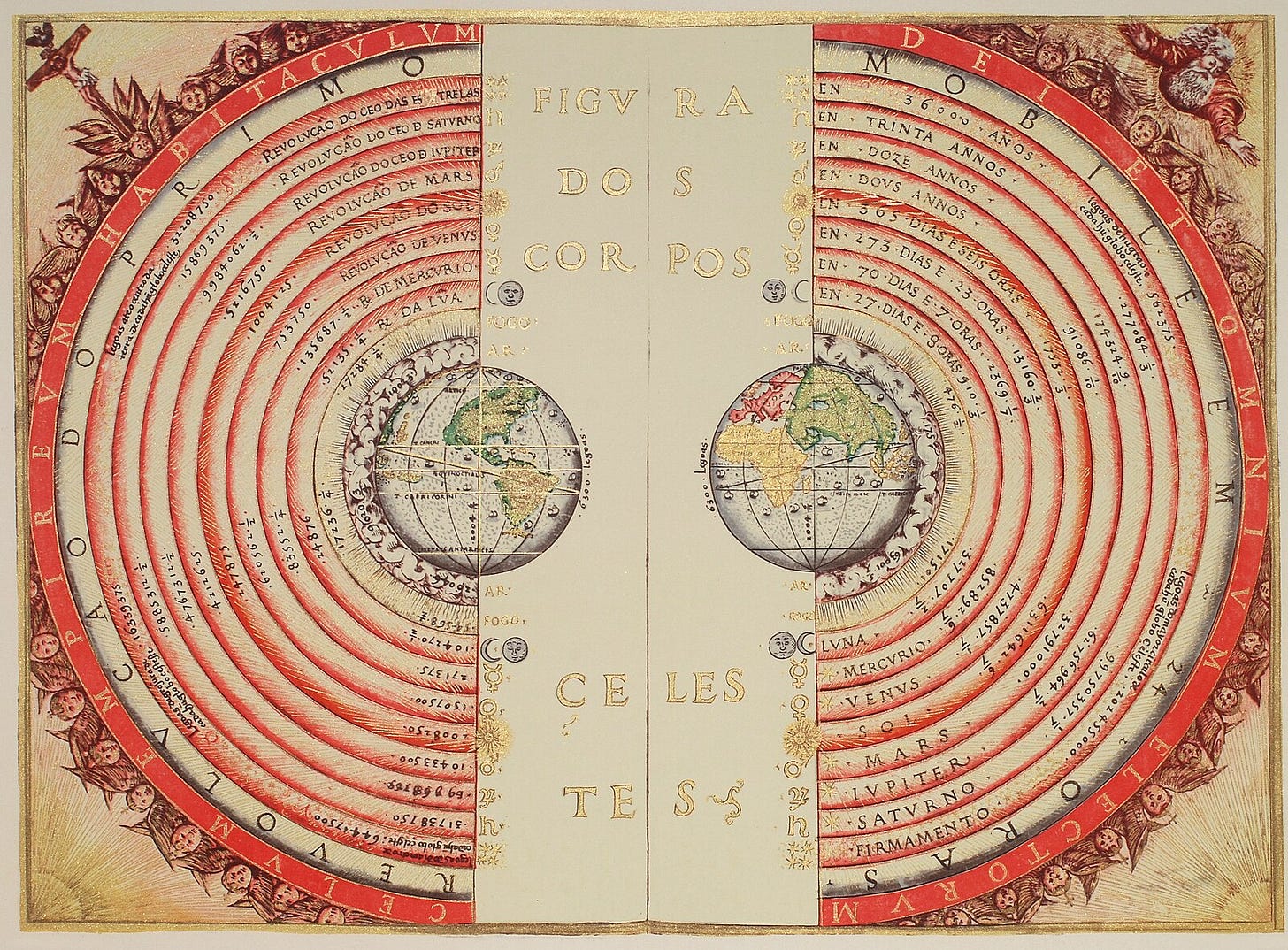

The easiest way I’ve found to wrap my head around it is to remember that the ancients of the Mediterranean believed that they lived in a cosmos — which is a bit different than the universe multiverse which we live in today. The Aristotlean-Ptolemaic cosmos which arose at around this time and place was framed as a series of concentric spheres, fitting inside one another like so many Russian dolls:

This helpful diagram, produced in the 16th century but based on the Ptolemaic cosmos, illustrates these concentric spheres nicely. The globe of the earth sits at the center, whereas all of the celestial spheres radiate outward, from the planetary orbits all the way out to the ‘firmament’.

The farthest sphere, found even beyond Firmamento, is the Heaven of Christian mythology. The Latin contained in this bold red band, rendered as Caelum empireum habitaculum Dei et omnium electorum, translates into something like: “The heavenly ordered abode of God and all the saints” (literally, “the Elect”). And notice who’s hanging out with them in the upper-left corner.

How are we, mere mortals, born of dust to return to dust, supposed to reach that high? The answer is found in this chart, not as the furthest ring, but in the nearest: LUNA, the line indicated by four full moons and four crescent moons. The moon, which, in its fullness, exactly reflects the light of the sun in its size and shape, brings that light down to a level where it can be more accessible on earth. The pleroma (“fullness”) of the moon reflects the pleroma (“perfection”) of the sun, represented in the character of Jesus Christ. As “the one who knew the All” (another title given to Mary Magdalene by the Gnostic gospels), she can perfectly reflect the light of the Sun/Son to carry it, unfiltered and uncorrupted, to the souls awake in the dust.

This role fits well with her widow archetype, which is further explored in the Gnostic Gospel of Mary Magdalene. That fragmentary gospel depicts a philosophical dialogue between Mary and the gathered apostles, still freshly grieving Jesus’ death. While we don’t have the space here to go into all the finer points, I wish only to emphasize that that gospel depicts Mary as the spiritual leader of the gathered group (although Simon Peter attempts to challenge her, he is quickly put in his place by the other apostles, who recognize Mary’s spiritual authority). As the one who remains behind, she provides a reflecting beacon for others — even Christ’s closest apostles — to follow.

It is in this way that, I believe, the character of Mary Magdalene evokes the same kind of radical reinterpretation of the Roman imperial religion that the character of Christ did. Whereas the divas like Livia Drusilla were worshiped, in no small part, to emphasize the vast social distance between the elite Roman rulers and their far-flung subjects, Mary Magdalene finds her power in her radical accessibility. The One Who Knew the All is still among us, guiding the faithful back to their family in heaven.